February 16, 2023

The Murky Politics of Clean Water

Defining the “Waters of the United States” is crucial for wetlands protection, but it’s become increasingly politicized, putting Midwest waters at risk

Once upon a time, there was broad bipartisan support for strong federal clean water protections. The Clean Water Act (CWA) of 1972 passed the U.S. House by a vote of 366 to 11, and passed the Senate unanimously. President Nixon vetoed the bill, but within two hours, Congress overrode his veto, 247 to 23 in the House and 52 to 12 in the Senate, with 113 Republican members of Congress willing to defy the President.

“The kind of natural environment we bequeath to our children and grandchildren is of paramount importance. If we cannot swim in our lakes and rivers, if we cannot breathe the air God has given us, what other comforts can life offer us?” – Sen. Howard Baker (R-Tennessee, 1972)

As Sen. Howard Baker, a Republican from Tennessee, said on the floor at the time, “As I have talked with thousands of Tennesseeans, I have found that the kind of natural environment we bequeath to our children and grandchildren is of paramount importance. If we cannot swim in our lakes and rivers, if we cannot breathe the air God has given us, what other comforts can life offer us?”

Unfortunately, times have changed. Republicans have mounted a large-scale assault, in both Congress and the courts, to severely limit the reach of the federal Clean Water Act, and to return us as much as possible to the bad old days before the law was passed.

Why does this debate matter so much in the Midwest?

Simply put – wetlands. The main concern about what is or is not covered by the Clean Water Act revolves around protecting the dwindling wetlands we still have. As the science keeps confirming, wetlands provide a host of critical ecological services—soaking up floodwaters, recharging groundwater, storing carbon, providing wildlife habitat, filtering water, and holding polluted runoff. The Great Lakes, many of our smaller lakes, rivers, and streams, and many of our drinking water supplies depend on healthy wetlands to keep their water clean.

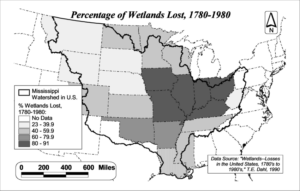

Map showing the percentage of wetlands lost in the United States are particularly acute in the Midwest. (Dahl, T.E. 1990) Click for full report

One of the central controversies today revolves around how to define the phrase “waters of the United States,” or “WOTUS,” which is what defines the Clean Water Act’s scope. If a lake, river, stream, or wetland counts as a “water of the United States,” the Clean Water Act applies; if it doesn’t, the waterbody is left either completely unprotected or subject only to state regulation.

The courts muddy the waters

For most of the last fifty years, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers—the federal agencies that administer the Clean Water Act—have operated under rules stating that WOTUS includes all “traditionally navigable waters” and their tributaries, and waterbodies that have a significant “physical, chemical, or biological” connection to them, including adjacent wetlands. Under the Act, no one may lawfully discharge pollutants, or dredge and fill material, into “jurisdictional” waters without a permit.

The main concern about what is or is not covered by the Clean Water Act revolves around protecting the dwindling wetlands we still have.

The application of those rules was unanimously upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1985 in a case called U.S. v. Riverside Bayview Homes, Inc., and the agencies continued to operate on that basis for the next twenty years.

In 2006, however, a new U.S. Supreme Court, with four Republican appointees who had come on the Court after Riverside Bayview Homes, revisited the question. In a case called Rapanos v. U.S, for the first time, a plurality of the Court decided that the agencies had been interpreting “waters of the United States” too broadly. Three Justices joined an opinion by Justice Scalia holding that only wetlands with a direct, continuous, visible surface water connection to other covered waters were protected by the Act. Four other Justices voted to uphold the broader view that Congress intended WOTUS to extend to the limits of Congress’s constitutional authority, but Justice Kennedy laid out a third position, concluding that adjacent wetlands could be covered, but only if they had a “significant nexus” with other jurisdictional waters.

Back & forth under Obama & Trump

Without a majority of the Court in favor of any single interpretation, the agencies spent years issuing new guidance documents trying to construe the Rapanos decision. In 2015, however, the Obama administration adopted a new formal rule, adhering to the “significant nexus” test but also clarifying with greater specificity which waters were covered and which were not. The goal was to adopt “bright line” rules that would give developers more certainty, but still protect the nation’s waters.

The narrower rule under Trump made no attempt to address the solid scientific consensus that wetlands play a major role in preserving water quality.

Nevertheless, the Obama rule proved to be controversial, and it had a rocky ride in the courts, with some courts upholding it and others prepared to drop it. In 2020, however, the Trump administration adopted its own rule, repealing the Obama rule, explicitly rejecting prior precedent and expressly declaring its intent to codify Justice Scalia’s plurality opinion in Rapanos into law. The new narrower rule made no attempt to address the solid scientific consensus the EPA compiled in what it called its “Connectivity Report” that wetlands without a visible surface water connection often play a major role in preserving the water quality in downstream lakes and rivers, either because of groundwater or other “physical, chemical, or biological” connections or because they hold pollutants that would otherwise travel downstream. A federal district court in Arizona rejected the Trump rule, and in early 2021, the Biden administration rendered the Trump rule inoperable by ordering the agencies to return to what had been the law before either the Obama or Trump rules had been adopted.

Biden goes back to the way things were before

On December 30, 2022, the Biden administration adopted its own new rules defining the term “waters of the United States.” The new rules are largely a return to the way EPA and the Corps had been implementing the law at least since the mid-1980’s, before either the Obama or Trump rules were promulgated, and they reflect the way the agencies are operating today.

It demonstrates how something as basic as clean water has become a divisive partisan issue.

Not surprisingly, however, the lawsuits were again flying in February 2023, and now Republicans in the House and Senate are trying to use a tool called the Congressional Review Act to erase this new rule from the books and prevent the agencies from ever adopting something similar. That will not pass, and if it did, President Biden would veto it, but it demonstrates how something as basic as clean water has become a divisive partisan issue. Many Midwestern Republicans who have consistently supported funding for Great Lakes restoration will, unfortunately, likely vote to kill the federal clean water protections the Great Lakes need to stay healthy.

Protecting the Great Lakes means protecting Midwest wetlands

In the Great Lakes region, we have already lost two thirds of the wetlands we once had. That loss of wetlands will continue unless effective federal and state regulation curtails it, and the Biden administration’s decision to return to the old rules is an important first step.

At the same time, however, the U.S. Supreme Court currently is considering again whether to force the Corps and the EPA to give up jurisdiction over all but those “direct surface water connection” wetlands. The case is called Sackett v. EPA, and it was the first case argued in the current Supreme Court term. The decision could come down any day. The fear, of course, is that the new conservative supermajority on the Court could force the agencies to go back yet again to the narrow reading of the statute Justice Scalia and the Trump administration adopted, or go even further to limit the reach of the Clean Water Act. On the other hand, it could decide the case on narrow factual grounds, and avoid making any broad changes in the law. ELPC will of course be ready to respond to the Court’s decision.

The decisions at the federal level are critical if we are going to have any way to preserve these vital natural resources.

No matter what the Court does, or, for that matter, what the federal agencies do, the states will retain the authority to adopt or enforce stronger wetland protections. In the Midwest, the states unfortunately have a spotty record at best, and some – including Ohio – have already decided that if the Court narrows the scope of the Clean Water Act, they will do the same. The decisions at the federal level are critical if we are going to have any way to preserve these vital natural resources. ELPC is watching the Court and watching Congress right now, and is ready to weigh in if and when the Biden administration responds.