June 18, 2024

Timber Targets Have Environmental Consequences

The Forest Service sets mandatory logging targets for national forests, but doesn't consider environmental consequences. An innovative lawsuit may change that.

by Jackson Darby, ELPC Legal Intern 2024

A lawsuit filed by the Southern Environmental Law Center (SELC) on behalf of the Chattooga Conservancy, Mountain True, and a Missouri citizen challenges the process of setting timber targets without conducting a proper environmental review. The U.S. Forest Service’s mandatory targets determine the amount of timber that must be logged from national forests every year. The lawsuit and revelatory internal Forest Service documents show how powerful these timber targets are in guiding Forest Service actions, often at great cost to the environment.

Private Loggers in Public Spaces

Only 31% of forest land in the United States is owned and managed by the federal government, and another 11% is owned by the state or local government. The rest is privately owned and largely unregulated by the federal government. Regardless, the United States government allows the private timber industry to log from publicly owned land to the tune of $3 billion each year.

The SELC has found that the major federal actions through which the Forest Service allows private loggers to extract timber from our national forests have extensive faults and constitute numerous violations of federal law. One might like to believe that the Forest Service determines the amount of timber that must be removed from national forests based on environmental circumstances, but this is far from reality.

As the parent agency to the Forest Service, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) sets a mandatory national timber target for the Forest Service to meet by logging our national forests, and it does so without considering environmental consequences as required under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). The USDA conducts no environmental review as to the environmental consequences of logging billions of board feet when setting those targets.

Even when the Forest Service takes the USDA’s national target and then sets regional targets, no environmental review is conducted. It is only when specific timber projects are proposed that any extensive environmental review might be required. Even then, such a review will be conducted only if the Forest Service finds that the project will have a significant environmental impact.

Even when the Forest Service takes the USDA’s national target and then sets regional targets, no environmental review is conducted. It is only when specific timber projects are proposed that any extensive environmental review might be required. Even then, such a review will be conducted only if the Forest Service finds that the project will have a significant environmental impact.

This process incentivizes profit-driven decision-making from Forest Service leaders and prioritizes timber production over other forest uses, such as water, wildlife, fish, and outdoor recreation. Unlike with timber production, there are no mandatory targets set for other mandated forest uses. The Multiple-Use and Sustained Yield Act (MUSYA) expressly prohibits the Forest Service from favoring one use of our national forests over another, but timber production has been an absolute priority for the Forest Service.

Shocking Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Findings

The SELC’s investigation of Forest Service timber-industry activity reveals that the Forest Service does, in fact, engage in exactly the sort of profit-driven decision-making that these timber targets would seem to encourage. Internal communications from the Forest Service show that the Forest Service’s efforts to meet its timber targets severely interfere with the agency’s ability to conduct “basic maintenance” in the forests, and to “respond to needs resulting from catastrophic events (e.g. fire) in a timely manner.” SELC found that in one instance, the Forest Service diverted federal funds intended for a wildlife habitat improvement project to “meet timber targets.”

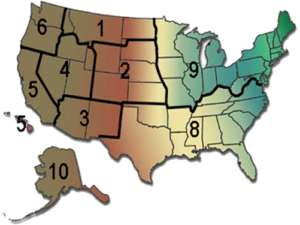

U.S. Forest Service Regional Offices generally cover multiple states.

Internal communications show that Forest Service employees clearly set their priorities in accordance with timber targets, to the detriment of other Forest Service obligations. The SELC has shown that fulfillment of timber targets “is used as a performance element for line officers, [interdisciplinary team] members, and others” within the agency. (1) As a consequence, Forest Service staff routinely choose to “prioritize ecological restoration projects that result in timber volume sold” over projects with potentially more critical restoration needs but lower timber volume to “ensure they meet” their timber targets. (2)

The Forest Service has made this point loud and clear. In Region 8, timber volume “is always at the forefront of the decision-makers thought process”, and “achieving timber targets is the region’s #1 priority.” (3) Likewise, within Region 9, timber volume targets must “take priority” over other agency activities. (4)

Timber Targets Undercut Mature and Old-Growth Protections

The ELPC has observed this attitude in practice in the Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest’s Fourmile Project, in Wisconsin’s Northwoods. Hundreds of thousands of trees that qualify as “old-growth” are being cut, mostly for pulpwood to make paper products.

Forest Service diverted federal funds intended for a wildlife habitat improvement project to “meet timber targets.”

Because bigger trees provide more “board feet” of timber (a board-foot measurement equivalent to a volume of lumber twelve inches long, twelve inches wide, and one inch thick), mandatory timber targets increase pressure on Forest Service staff to cut larger trees by any means possible.

This attitude stands in stark contrast to the public’s perception of what constitutes quality forest management. A poll completed by the National Forest Foundation found that 7 of 10 voters from across the political spectrum agreed that one of the things the U.S. government does best is protect and preserve the country’s natural heritage through National Forests. However, it seems the public is unaware that the Forest Service prioritizes harvesting forests as a commodity crop for private industry over protecting our natural heritage.

Timber Targets Undermine Efforts to Stop the Climate Crisis

The Biden administration’s bold efforts to transform the timber industry by protecting mature and old-growth forests and to fight against climate change have not registered with the Forest Service. While 2023 was the warmest year since global temperatures have been recorded, the USDA has nevertheless chosen to prioritize timber harvesting over the past decade. The Forest Service, itself, has boasted that the amount of timber sold from our national forests in recent years has been “higher than [in] any period in the previous decades” and that the Forest Service intends “to increase the level of timber volume sold” even further in coming years.

If the Forest Service were properly considering environmental and climate-change concerns in setting timber targets, it would be extremely difficult for Forest Service administrators to reconcile this expanding policy of deforestation with the Biden administration’s stated goals of preserving wildlife habitat and reducing the impacts of climate change.

If the Forest Service were properly considering environmental and climate-change concerns in setting timber targets, it would be extremely difficult for Forest Service administrators to reconcile this expanding policy of deforestation with the Biden administration’s stated goals of preserving wildlife habitat and reducing the impacts of climate change.

The negative effects of excessive logging on climate change are undeniable. Trees are our best tool to capture carbon dioxide from the air, as they can store this carbon in every part of themselves and in the ground. The cutting, then, of mature-growth and old-growth trees under the eyes of the Forest Service is particularly concerning, as these trees comprise the most carbon-dense forests (and are the most effective at carbon sequestration). (5)

Disrupting the ecosystem of a healthy forest has devastating effects to carbon sequestration. Soil carbon represents about 50% of the total carbon stored in forest systems in the US, and that carbon is released when soils are disturbed significantly, i.e. during logging operations.

Conclusion

The Biden administration has established promising federal policies to confront the climate crisis, including conserving the nation’s remaining mature and old-growth trees. But there is a stark disconnect between those policy intentions and the Forest Service’s actions, particularly regarding timber targets and logging.

The SELC’s complaint argues that environmental considerations must be considered when the amount of timber logged from our national forests is decided. This decision has massive cumulative environmental consequences and should, therefore, be reviewed under NEPA at every planning level. Forest Service timber projects must not advance solely to meet their 2024 targets before undergoing an environmental review of the targets themselves.

Footnotes:

- U.S. Forest Serv., Daniel Boone Nat’l Forest, Timber Sale Schedule Expectations (Jan. 10, 2024)

- Email from Alyson Warren, Region 6 Assistant Director of Natural Resources, to Jose Castro, Region 8 Director of Forest and Timber Management (Nov. 15, 2019)

- U.S. Forest Serv., Region 8, FY2020 Budget Request (2019), U.S. Forest Serv., Region 8, Forest Management and Timber Staff Unit Expertise and Priorities (May 3, 2019)

- U.S. Forest Serv., Ottawa Nat’l Forest, Integrated Unit Program Development Narrative at 9 (2019)

- Secretary of Agriculture Memorandum 1077-004, Climate Resilience and Carbon Stewardship of America’s National Forests and Grasslands (June 23, 2022).