Snowmelt pools on a roadside

January 20, 2023

Winter Manure Spreading is Bad for Midwest Water

Frozen ground can’t absorb nutrient pollution, so it washes away and affects communities downstream.

Winter manure spreading on frozen fields

It’s officially winter: across the Midwest, snow has started to fall and the annual tradition of complaining about the cold – or complaining about people who are complaining about the cold – has begun. Unfortunately, a much more dangerous annual tradition may be around the corner as well. Each winter, millions of gallons of CAFO manure and other waste is spread on frozen or snow-covered land across the Midwest. This practice, known as winter spreading, is uniquely dangerous to water quality; in many cases, it is also illegal. But many states don’t have the staffing or resources to enforce these restrictions, and they depend on citizen complaints and self-reporting. The practice is, unfortunately, all too common.

The Problem:

Over the past 30+ years, concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) have transformed livestock agriculture – as well as rural communities – and not for the better. Traditional, diversified farms (think of the classic, red barn “family farm” of popular imagination) kept a manageable number of animals at pasture, and any manure the animals produced was used to fertilize crops on the farm. But this natural system of nutrient intake (grazing) and output (dropping manure) was blown apart by the CAFO business model, which rose to prominence in the 1990s.

Cows graze in an Iowa field and stream Photo by Warren Taylor

Nearly 3,000 independent family farms – particularly dairies – have gone out of business in Wisconsin, and in Missouri, 90% of independent hog farmers have gone out of business in the past generation. In 2022, research indicated that suicide rates among farmers are 5 times higher than the national average – even double the rate for military veterans.

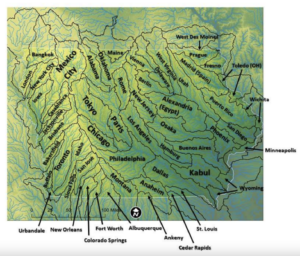

CAFOs keep thousands (sometimes tens of thousands) of animals in confinement and, as a result, generate far more feces and other waste (urine, milkhouse waste, washing water, etc.) than nearby fields can absorb as fertilizer. In fact, an average CAFO can produce as much waste as the city of Philadelphia. This leads to an excess of CAFO waste being spread on relatively small land areas nearest CAFOs. This is a problem because CAFO waste contains pathogens such as E. coli, pharmaceuticals, and nutrients (such as nitrogen and phosphorus), all of which can damage water quality.

Waste equivalent produced by animal agriculture in Iowa. (Click to Expand) Credit: Christopher Jones at Iowa Academy of Science

In manageable amounts, nutrients can act as fertilizer, but in excess, these nutrients can be deadly. Excess phosphorus runs into rivers and lakes, feeding the harmful algal blooms (HABs) that have choked the Midwest’s waters for years; most infamuosly, Lake Erie. And excess nitrogen can lead to nitrate exposure via drinking water, which has been linked to cancer, miscarriage, diabetes, and a potentially lethal disease called blue baby syndrome.

Unlike human waste, which must be treated before it is disposed of, CAFOs are allowed to spread waste on land untreated. In areas that are already over-saturated with nutrients – i.e., areas near CAFOs – land spreading is effectively waste disposal masquerading as crop fertilization, devoid of any agronomic rationale. Winter spreading is even less justifiable. It provides no agronomic benefit whatsoever, since there are no crops in the ground during winter to take up any nutrients. And even if there were, frozen ground is impervious, so the nutrients can’t physically get into the soil to become available for crop uptake. Instead, the waste remains on the surface and either runs off with snowmelt or (depending on soil type and hydrology) leaches into groundwater when the ground thaws.

Bottom Line:

Algae in water

Overapplication of CAFO waste is harmful any time of year, but it is particularly pernicious – and unjustified – during the winter months. CAFOs produce too much waste and they are subject to uniquely and inappropriately lax regulatory oversight. States need to step up enforcement to protect our waters from harmful algal blooms, nitrate poisoning, and other harmful effects of CAFO waste.

ELPC is working to rein in manure pollution, stop toxic algae, and protect clean water in Ohio, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Iowa. We can’t take water quality for granted just because it’s winter. It’s time that big business got the message, and regulators stepped up to protect the Midwest.