Kennedy Expressway, Chicago

March 13, 2023

30 years of Advocating for “Fix it First” Transportation Policy

A look back on how ELPC has held the line on roadway expansion and shaped the conversation for better transportation.

For almost thirty years, ELPC has been engaged in a fundamental debate over the purpose of transportation. Is our goal to move cars quickly? Or is it to safely connect people with jobs, family, and other needs?

Back in 1993, states resoundingly would have answered the former. Pointing to growing congestion, they argued that new road capacity was desperately needed in and around our cities and towns. We disagreed, opting for a “fix it first” approach, to discourage boondoggle road projects while advancing the sustainable transportation solutions that work.

Today, this debate is more vital than ever, as President Biden’s Bipartisan Infrastructure Law offers a once-in-a-generation opportunity to fix our roads and bridges. States and municipalities can seize the chance to catch up on the backlog of infrastructure maintenance that has plagued us for years, or they can waste it on new roads we can’t afford to maintain. Transportation is now the leading source of carbon emissions, so the decisions we make today could lock us into even more costs down the line. Fortunately, communities are increasingly calling for sustainability, safety, and fiscal responsibility, values that ELPC continues to champion through our transportation team. Here’s a look back on how we’ve held the line on roadway expansion and shaped the conversation for better transportation.

When it comes to road building, more is not better

- Creating new road capacity never solves congestion because it merely encourages people to drive more, a process known as “induced demand.” Over the last 30 years, the United States has paved faster than we’ve grown, adding 42% more lane miles compared to only 32% more people.

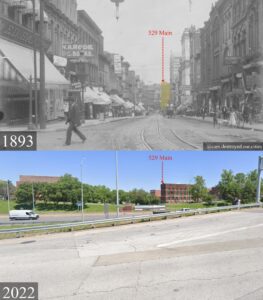

Highways made American cities less walkable and more difficult to traverse without a car. Click to read more about Kansas City, MO.

Nonetheless, congestion ballooned by 144%. As roadways get bigger, developers build destinations further away from one another. Walking, biking, and public transportation become more difficult, so we become more dependent on driving, and the cycle continues. We have been trying to pave our way out of congestion for decades, and it has only made things worse.

- Additional roads are expensive. The more we build, the more we have to maintain. There are always new potholes, but there is never enough money to fix them all. As highways spread the population more thinly over a wider sprawling area, the less people there are to pay for each square foot of infrastructure. Contrary to the myth that roads “pay for themselves” through the gas tax, Congress has continued to increase highway spending without raising the gas tax since 1993. Midwest states have raised their own gas taxes, but a lot of road funding today now comes from sales, property, and income taxes. Sure, our roads need repair. But if we are paying for them with anything other than user fees, we’re subsidizing drivers and encouraging people to drive more.

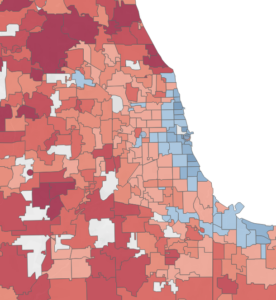

- More driving means more air pollution, more traffic deaths, and more global warming. Suburban and exurban residents have a much larger carbon footprint than those living in the urban core, as you can see in this map. Transportation is the leading source of carbon emissions in the United States, largely fueled by gas cars, trucks, and SUVs.

So how to revitalize our cities and reduce pollution? ELPC’s answer was to oppose misguided transportation projects that were making the problems worse.

Bad proposals weren’t hard to find:

- ELPC and partners spent decades fighting Illinois Department of Transportation’s (IDOT) efforts to build a second beltway of highways around Chicago, extending I-355 and turning Route 53 into a limited access tollway. We successfully prevented construction of three out of four segments of this road. In one case the court agreed with us that Illinois DOT was engaged in circular logic: the highway was needed because of projected traffic growth, but the traffic growth would be caused by building the highway.

- A few years later, lawmakers proposed a THIRD ring road around Chicago – the infamous “Hastert Highway” – more than 40 miles from Chicago’s downtown Loop. The project earned that moniker because then-Speaker of the House Dennis Hastert (R-IL) secured a $207 million federal earmark for the billion dollar boondoggle which just so happened to run past farmland he held in a secret trust. Thankfully, the road was never built.

-

Proposed Illiana Expressway corridor, Wikimedia map.

The proposed Illiana Tollway, which would parallel I-80 far south of Chicago, was similarly misguided. The projected vehicle traffic that would have used this road was so small that, according to federal safety guidance, kids could have safely walked across the road to school. On this “public-private partnership,” tolls would have covered just a tiny fraction of the road’s cost, leaving taxpayers holding the bag. The deal even included a guarantee that private investors would be paid back in full regardless of whether tolls brought in sufficient revenue. By stopping this unnecessary highway, ELPC also helped protect the Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie, (one of the prairie state’s few remaining patches of its namesake ecosystem), which was adjacent to the projected tollway route.

- Adding insult to injury, the Illiana tollroad would have supported the equally unnecessary Peotone Airport. Decades ago, when it looked like expanding O’Hare airport was impossible, the farmland around Peotone looked to some like an attractive location for an airport to capture this overflow traffic. When O’Hare expanded, the logic for this exurban boondoggle evaporated. But support for this third airport persists to this day, so ELPC continues the fight.

-

Petoskey, Michigan. Credit: Todd Van Hoosear

In 2002, we persuaded Michigan’s Department of Transportation (MDOT) to abandon plans for a damaging and disruptive four-lane bypass through the scenic and rural area of Petoskey in the northern part of the lower peninsula. Instead of building a bypass that would not solve congestion issues and would have destroyed wetlands, farms, and the historic community character, MDOT decided to support a transportation and land use planning process. Led by local citizens and governments, the new plan wisely focused on reinvestment in and upgrades to existing roads.

- Ironically, Illinois took the opposite tack in an attempt to build a new Shawnee Parkway in southern Illinois, arguing that a population decrease was justification for a new road which would bring with it renewed economic activity. As we wrote in our official comments, “IDOT simply cannot have it both ways. It is absurd to claim that when an area is growing, the state should build a highway to accommodate this growth, and when an area is declining, the state should build a highway to create growth. By this logic, Illinois should be building highways literally everywhere, a position which is certainly not consistent with smart transportation planning.”

It is absurd to claim that when an area is growing, the state should build a highway to accommodate this growth, and when an area is declining, the state should build a highway to create growth. By this logic, Illinois should be building highways literally everywhere

We fought to protect the environment and ended up saving taxpayers billions of dollars that would have been wasted on unnecessary road projects. We urged states to adopt “fix it first” priorities and we’ve helped countless colleagues in their own fights against misguided highways around the region. We have advocated for safe, efficient, and affordable transportation solutions that get people out of cars and give them the option to walk, bike, or take public transportation to reach their destinations.

We’ve made tremendous progress over the past three decades. Ill-considered highway and airport proposals have slowed to a trickle across the Midwest. Our best hope is that state Departments of Transportation finally realize that multi-modal road safety, transit, and maintenance are where they should focus their attention. Or perhaps the states have just run out of money for boondoggles, as highway construction costs climbed, and politicians have been reluctant to raise gas taxes to fund these endeavors.

Public transportation, walking, and biking have much more efficient land use than driving. Source: Australia’s Cycling Promotion Fund

But our work is not done here. The Biden administration’s Bipartisan Infrastructure Law includes a lot of money for transportation infrastructure. So, will all this money make the problem worse or better? That depends how it is spent. The Georgetown Climate Center concludes that “If transportation investment decisions prioritize a “fix it first” approach and emphasize maintenance of existing roadways, along with investments in transit, electric vehicles and charging infrastructure, and other low-carbon transportation options, this historic infusion of federal funding has the potential to accelerate reductions in (greenhouse gas) GHG emissions from surface transportation relative to business as usual.” But if the money is spent instead on road-building, the problem will get worse.

With 30 years of experience, ELPC continues the fight to ensure that state and federal infrastructure dollars are spent wisely to “fix it first,” move people around efficiently, and reduce transportation’s impact on climate change.